This November, Adam Barnhardt, Mofart Ayiega, Rose Fisher, Jess Shepherd, Connor Bechler, Annan Kirk, and Karthik Durvasula will be presenting at NWAV 53 (New Ways of Analyzing Variation) at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor!

- Adam will be presenting “Creaky voice: A women-led sub/exurban-centric sound change in white Michigan English“

- Mofart will be presenting “Morphological Non-agreement on Animate Nouns in Swahili“

- Rose will be presenting “Language Loyalty and Maintenance: The Case of Pennsylvania Dutch“

- Jess will be presenting “Paths of sound change in the [mɪɾən]: /tən/ in two varieties of Michigan English”

- Connor will be presenting “Modeling and Documenting Variation across Pumi Varieties“

- Annan Kirk will be presenting “Really is really frequent: intensifiers and change in Michigan English“

- Karthik will be presenting “Near mergers are compatible with categorical representations”

NWAV 53 will run from Nov. 5th – 7th. Register here.

Click ‘Continue Reading’ for abstracts.

Abstracts

Creaky voice: A women-led sub/exurban-centric sound change in white Michigan English (Barnhardt 2025)

Creaky phonation (creak) has been shown to be used more by women in some English varieties (Podesva, 2013; Yuasa, 2010; Abdelli-Beruh et al., 2014; Wolk et al., 2012). Increasing rates of creak across apparent time and the expansion of creak’s prosodic domain have also been attested (Callier & Podesva, 2015; Penney, 2015). However, some analyses have argued against a sound change/women-predominant interpretation of creak variation in English (Brown & Sonderegger, 2024; Oliveira et al., 2016). In this paper, I investigate the age, gender, and urban-rural distribution of creak in white Michigan English, both overall and across phrasal positions.

Morphological Non-agreement on Animate Nouns in Swahili (Ayiega 2025)

This study investigates morphosyntactic variation in Swahili verbal agreement, focusing on non-canonical subject-verb agreement with animate nouns in noun classes 1 and 2. While much sociolinguistic research has centered on phonological and phonetic variation (Anttila, 2018; Eckert, 1989; Labov, 1994; Tagliamonte, 2012; Wagner et al., 2016), often because such change is faster and easier to observe (Labov, 2006; Nagy, 2013), variation above the level of phonology, especially in morphosyntax, remains understudied due to challenges in defining semantically equivalent variants (Lavandera, 1978; Romaine, 1981). This study addresses this gap by exploring verbal prefix variation in Swahili, a Bantu language with a rich noun class system. To my knowledge, this variability has not previously been reported in detail. Swahili nouns are organized into morphological classes based on semantics and number. For instance, noun, like m-toto ‘child,’ is in Class 1, while its plurals, wa-toto ‘children,’ fall into Class 2. Verbs must agree morphologically with the nominal subject: nouns from Classes 1 and 2 require subject markers (SMs) a- and wa-, as in (1) and (2). However, animacy can override canonical agreement patterns (Pesetsky, 2019). Class 9/10 nouns typically take the prefixes i- (singular) and zi- (plural), but when the referent is animate, the expected verbal prefix shifts to a-/wa- instead, as in (3a, b) for inanimates and (4a, b) for animates.

From pilot data collected in Nairobi among young adult speakers aged 18–28, three major types of variation emerge. First, some speakers use the inanimate i-/zi- agreement consistently even for animate Class 9/10 nouns, as in (5a, b). This reflects a trajectory toward full paradigm leveling, where speakers are ignoring semantic animacy distinctions. Second, some speakers make a distinction based on whether an animal is alive or dead. In this case, a-/wa- is reserved for living animals, while i-/zi- is used for dead ones, as in (6a, b) and (7 a, b). Third, some Class 9/10 nouns (especially those lacking an overt nominal prefix, such as samaki ‘fish’) also exhibit subject agreement variation. In Standard Swahili, these zero-prefix nouns typically take a-/wa- agreement (see 8a, b), but among speakers, they may also appear with i-/zi- agreement (see 9a, b). This suggests that even morphologically unmarked nouns are subject to shifting patterns of agreement. Such variation likely reflects the influence of Nairobi’s multilingual environment. As Cheshire et al., (2011) and Nassenstein (2019) observe, multilingual youth often draw from a morphosyntactic “feature pool” shaped by contact and mobility. This study examines if and how variation is conditioned by language-internal features (e.g., noun class, animacy, number, prefix presence) and social factors (e.g., age, gender, L1 background, and style). Data were collected through a picture description task and a sociolinguistic interview, each designed to elicit both formal and casual speech. Drawing on Labov (1972), interview prompts include culturally familiar topics like childhood games and visits to local parks to stimulate discussion of animal referents. The study shows that noun class simplification and leveling stem from ongoing change in progress.

(1) M-toto a-na-chek-a.

1-child 1SM-PRT-laugh-FV

‘The child laughs.’

(2) Wa-toto wa-na-chek-a.

2-childern 2SM-PRT-laugh-FV

‘The children laugh.’

(3) a. N-yumba i-na-anguk-a.

9-house 9SM-PRT-fall-FV

‘The house is falling.’

b. N-yumba zi-na-anguk-a.

10-houses 10SM-PRT-fall-FV

‘The houses are falling.’

(4) a. N-g’ombe a-na-ku-l-a ma-jani.

9-cow 1SM-PRT-INF-eat-FV 6-grass

‘The cow is eating grass.’

b. N-g’ombe wa-na-ku-l-a ma-jani.

10-cows 2SM-PRT-INF-eat-FV 6-grass

‘The cows are eating grass.’

(5) a. Ng’ombe i-na-ku-l-a ma-jani.

9-cow 9SM-PRT -INF-eat-FV 6-grass

‘The cow is eating grass.’

b. N-g’ombe zi-na-ku-l-a ma-jani.

10-cow 10SM-PRT-INF-eat-FV 6-grass

‘The cows are eating grass.’

(6) a. N-gamia a-na-ku-nyw-a maji

9-camel 1SM-PRT -INF-drink-FV 6.water

‘The camel is drinking water.’

b. N-gamia wa-na-ku-nyw-a maji

10-camels 2SM-PRT-INF-dead-FV 6.maji

‘The camels are drinking water’

(7) a. N-gamia i-me-ku-f-a

9-camel 9SM-PRF-INF-dead-FV

‘The camel is dead.’

b. N-gamia zi-me-ku-f-a

10-camels 10SM-PRF-INF-dead-FV

‘The camels are dead.’

(8) a. Ø-samaki a-na-og-e-le-a

9.fish 1SM-PRT-swim- APPL-STAT-FV

‘The fish is swimming.

b. Ø-samaki wa-na-og-e-le-a

10.fish 2SM-PRT-swim-APPL-STAT-FV

‘The fish are swimming.

(9) a. Ø-samaki i-na-og-e-le-a

9.fish 9SM-PRT-swim-APPL-STAT -FV

‘The fish is swimming.’

b. Ø-samaki zi-na-og-e-le-a

10.fish 10SM-PRT-swim-APPL-STAT -FV

‘The fish is swimming.’

Language Loyalty and Maintenance: The Case of Pennsylvania Dutch (Fisher 2025)

Introduction: Pennsylvania Dutch (PD) is a German variety spoken by multiple groups in North America. These groups vary widely in how well they have maintained the language and how much they separate themselves from mainstream society. On the one hand, Lutheran and German Reformed PD speakers have completely assimilated with mainstream society and retain very few native speakers. On the other hand, more conservative and separatist Amish and Mennonite groups have more successfully kept the encroachment of English at bay. The most separatist of these groups continue to pass the language on to their children (Louden 2016). Keiser (2003) explored to what extent the move toward off-farm work and the resulting greater exposure with the outside world in many Amish communities could contribute toward the eventual loss of PD. He compared two Amish communities, one large one in Holmes County, Ohio and another smaller one in Kalona, Iowa. He concluded that the move toward off-farm work, what Kraybill (2001) has dubbed “the lunch pail threat,” has resulted in more English use and less prestige for PD in Kalona, but that these findings do not necessarily hold for Holmes County, Ohio, where the large number of Amish supports PD maintenance even in many workplaces.

Research Question: Are the Mennonites, who continue to farm more and interact less with outsiders, more loyal to PD than the more technologically conservative Amish?

Methods: The data used for this analysis come from sociolinguistic interviews conducted with 45 native PD speakers. Seventeen of the speakers come from the Old Order Mennonites of Lancaster, Berks, and Union Counties in Pennsylvania. The remaining twenty-eight speakers come from the Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. A combination of qualitative and quantitative responses to questions about language proficiency, maintenance, and loyalty are analyzed.

Results: When loyalty is operationalized as the importance of children and grandchildren learning to speak PD (value) and whether or not one can still be Amish/Mennonite and not speak PD (identity), the Mennonites and Amish do not really differ. They both consider PD to be a valuable but non-essential component of their ethnoreligious identity. When loyalty is operationalized in terms of language use and familiarity, however, clear group differences emerge. The Amish use a much higher proportion of English, including in domains historically reserved only for PD (e.g., the home), compared to the Mennonites. They also more often judged themselves to be more (or as) comfortable speaking English in comparison to the Mennonites.

Conclusions: These results support the conclusion that the “lunch pail threat,” or move off the farm, does contribute to the increasing use of English among the Amish. The proportion of English spoken within the Amish community is growing, even while many of them remain loyal to PD in attitude. Due to their greater separation from mainstream society, the Mennonites are better able to keep the encroachment of English at bay. This work contributes to our broader understanding of interplay between separatism and PD maintenance and loyalty.

Paths of sound change in the [mɪɾən]: /tən/ in two varieties of Michigan English (Shepherd 2025)

In American Englishes, post-tonic /tən/ (such as button), is typically produced as either [tən] or [ʔn̩]. In recent years, researchers have noticed two potential changes in progress: the change from a syllabic nasal ([n̩]) to a vowel and nasal pair ([ən]) following [ʔ] (Eddington & Brown, 2021; Eddington & Savage, 2012; Repetti-Ludlow, 2024) and the change in /t/ from [ʔ] to [ɾ] (Eddington & Savage, 2012; Repetti-Ludlow, 2024; Stanley, 2023). There may be a feeding relationship between these two changes, with the change from [n̩] to [ən] creating the environment for the change from [ʔ] to [ɾ] to occur (Repetti-Ludlow, 2024). If this is the case, then we would expect a speech community to exhibit a change in /ən/ before a change in /t/, which Repetti-Ludlow and Blake (2023) found apparent-time evidence for in their experimental data. They also found a significant effect of ethnicity in the realization of /ən/, with Black-identified participants having higher rates of [ən] than non-Black participants. Therefore, they argued that this is a Black-led sound change.

In this talk, I investigate the historical changes in the realization of these relatively infrequent BUTTON words in Michigan through the use of apparent-time data from two large scale corpora. The first is the MI Diaries corpus (MDC), which is a collection of self-recorded ‘audio diaries’ containing naturalistic speech data from speakers in Michigan (Sneller & Wagner, 2020-). Due to the lack of a sufficient number of analyzable tokens from Black speakers in MDC, I supplemented it with data from the Detroit speakers in the Corpus of Regional African American Language (CORAAL) (Kendall & Farrington, 2023) to test Repetti-Ludlow and Blake’s (2023) ethnicity claim. A total of 85 speakers (57 from MDC and 28 from CORAAL) with tokens of post-tonic /tən/ were included in this analysis, resulting in 1214 tokens (1128 from MDC and 86 from CORAAL).

Each of these tokens was auditorially coded for the realization of /t/ ([t], [ʔ], and [ɾ]) and /ən/ ([n̩], [ən]). The CORAAL data shown in Figure 1 show an expected pattern of innovation between the two features. [ən] occurs early in the speech community, the earliest being from a speaker born in 1888. This change could enable these speakers to produce [ɾ]. However, the first token of [ɾ] comes later, first appearing in the speech of a participant born in 1903. Furthermore, none of the speakers in CORAAL produced [ɾn̩]. By contrast, the speakers from MDC do not show the expected pattern of innovation. Both variants appear around the same time (early 1950’s) and multiple speakers produce tokens of [ɾn̩]. These findings suggest that Black speakers in Detroit went through both sound changes at least a few generations before other non-Black populations in Michigan and that both changes were innovated endogenously in these Black speech communities. However, given the timing of the innovation in non-Black communities, I argue that the speakers from MDC borrowed these features when it was already a late-stage sound change for speakers of African American English in the area.

Modeling and Documenting Variation across Pumi Varieties (Bechler 2025)

In order to contribute to the nascent literature on the sociolinguistics of tone (Du, 2021; Perry, 2017; Stanford, 2008, 2016b; Stanford & Evans, 2012; Wang, 2020; Wang & Wagner, 2020; Zhang, 2019; Zhao, 2018) and increase the accountability of variationist theory to rural and indigenous speech varieties (Chirkova et al., 2018; Meyerhoff, 2019; Stanford, 2016a; Stanford & Preston, 2009), this work aims to provide the theoretical and empirical foundation for a future field project exploring tonal variation across varieties of Pumi, a Sino-Tibetan language spoken in Southwest China.

Pumi (also known as Prinmi) is a member of the Qiangic branch spoken by 40,000-70,000 people in the provinces of Yunnan and Sichuan (H. Daudey & Gerong, 2020). It is primarily unwritten, taught in only one school, and exhibits high levels of regional variation (H. Daudey & Gerong, 2018). Pumi possesses a complex tone system, with tone spreading and tone sandhi processes that are sensitive to both morphological and syntactic processes. As shown in Figure 1, each documented variety of Pumi displays a slightly different portfolio of tones and spreading behaviors (G. H. Daudey, 2014; Ding, 2014; Jacques, 2011; Matisoff, 1997), with even neighboring varieties’ tone systems differing substantially (Daudey and Gerong, 2024, p.c.). Any theory of Pumi tone must therefore be flexible enough to account for the observed variation between closely related varieties, while conversely, any variationist attempt to characterize Pumi tone must be careful in demarcating the correct envelope of variation to enable successful elicitation and analysis.

The present work aims to draw together existing descriptions of tone across Pumi varieties to operationalize several tone variables—the extent of tone spreading, the particular phonetic realization of tone contours, and the behavior of a particular class of “alternating” verbs—and develop methods for future fieldwork exploring how and why these variables are used differently across Pumi speakers and varieties.

To this end, I will present an initial model of Pumi tone spreading that accommodates variation—along the lines of Auger (2001)—supported by phonological comparison of Pumi varieties and phonetic evidence from of an existing Northern Pumi corpus. Following Ding’s (2001, 2014) analyses of tone in Central Prinmi and drawing on Zhang (2007) and Evans’ (2018) theories of tone spreading in Sino-Tibetan languages, this model posits that tone spreading is lexically specified, with cross-dialectal variation in spreading arising as a byproduct of different underlying tones, rather than different phonological processes.

I will also present the elicitation methods I intend to employ in interviews with Pumi consultants, particularly seeking feedback on how to address the challenge of eliciting formal speech without reading tasks, given that Pumi is unwritten. One potential method from the documentation literature involves asking consultants to repeat frame sentences to capture specific target words’ tone spreading behavior at different locations in an utterance (Niebhur & Michaud, 2015; Yu, 2014). To reduce bias from my production and also elicit more naturalistic speech, I may also ask consultants for feedback on my production and explanations of words’ meanings or use, seeking their correction and elaboration (Pérez, 2024).

Near mergers are compatible with categorical representations (Durvasula 2025)

Near mergers are often claimed to be a problem for categorical phonological representations (Labov 1994; Yu 2007). As I will argue through formalisation and simulations, the claim rides on conflating the distinction between a ‘category’ (or ‘phonological representation’), which refers to abstract cognitive objects that are manipulable by a computational system, and phonetic exponence. When the distinction is kept clear, all the facts of near mergers fall directly out of viewing phonological representations as categorical.

Near mergers have four typical characteristics: (a) Fact 1: the exponences of the two categories are phonetically close. (b) Fact 2: some speakers in the community show full overlap in exponences, while others don’t (Maguire, Clark, and Watson 2013). (c) Fact 3: such speakers have difficulty perceptually distinguishing the categories. (d) Fact 4: near mergers can sometimes be reversed, crucially without hypercorrection.

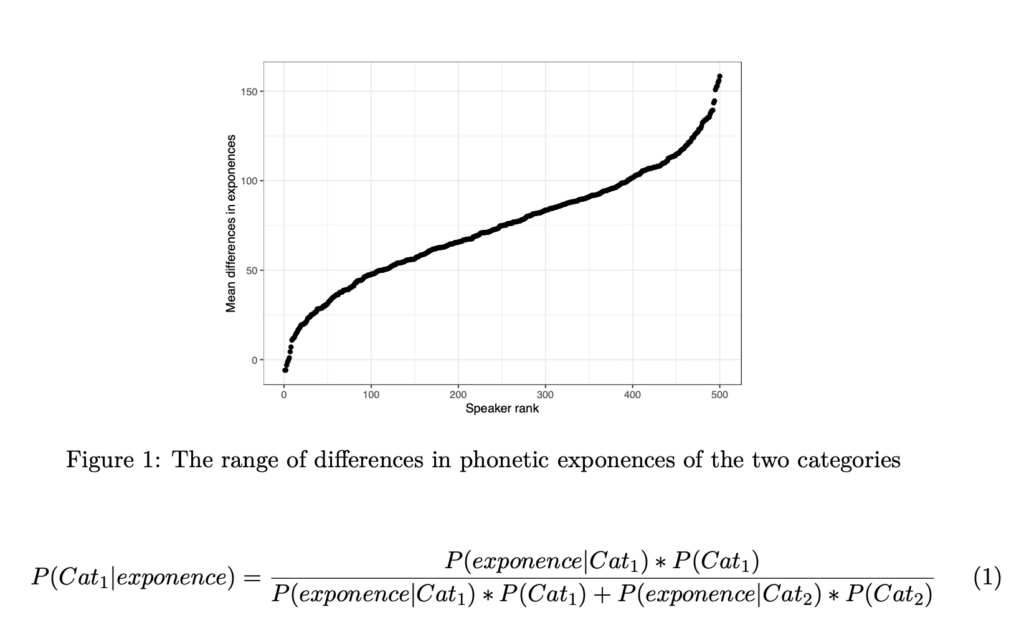

Formalisation and simulations: Categories can be formalised as random variables (C1 and C2). Two random variables are separate even if their means are close; therefore, categories can be distinct despite their exponences being close (Fact 1). Furthermore, there will be some variation in the observed differences in exponences between the categories between speakers. Finally, there will be a cline of differences between the exponences of the two categories. The last point can be seen through simulations.

Let’s assume the two categories are Normally distributed: Cat1∼N(µ = 500,σ = 75) and Cat2∼N(µ= 575,σ= 75). Further suppose there are 500 speakers who each produce 10 repetitions of each category and have the same category means and standard deviations. Then, the mean difference in exponences between the categories will form a cline, as in Figure 1, thereby capturing Fact 2. In fact, the observed speaker differences can vary between 0 to some large value, despite the fact that all the speakers have the same categories and the same phonetic distributions for each category. This suggests that differences between speaker exponences don’t automatically show that the underlying system is different for the speakers. Furthermore, the perceptual facts can be modelled using the same random variables in a Bayesian perceiver with the same category means and variances, and equal priors, using Equation 1. If productions are simulated from either category, the average identification probability for that category is about 60%, i.e., the identification is quite poor. Therefore, the formal model also captures Fact 3.

Discussion: The first three characteristics of near mergers are predicted when categorical representations are viewed as random variables with respect to phonetic exponence. Furthermore, that the categories themselves can be kept distinct even when the exponences are close automatically accounts for the fact that near mergers, unlike full mergers (Garde’s principle of irreversibility (Garde 1961)), can be reversed without hypercorrections (Fact 4). More generally, in making inferences about phonological categories, one must make precise and formalised claims about phonetic exponence — without formal modelling of the underlying structure, it is difficult to interpret the variation in phonetic manifestations as a reflection of the underlying representations or grammar.